|

| Entrance to the Petaluma Free Library Photo Courtesy of Jef Poskanzer |

The library is such an obvious public good, and so ubiquitous today, that it may be surprising to learn that it is a recent an addition to civic life. Of the thousands of public libraries in existence today in the United States, not one existed as a public library before the nineteenth century (Bobinski, 1969).

Clubs, fraternal societies, religious organizations, schools, businesses, governmental institutions and for-profit book-circulating enterprises all had their own collections with widely varying degrees of collection quality and ease-of access. Borrowing a book usually required paid membership, enrollment, or special dispensation. Notable libraries before the nineteenth century were either in schools, on private property or were assets of subscription-funded enterprises. For example, Harvard, as an institution is traced back to the eponymous donor’s contribution of his personal library of 280 books to the budding seminary in 1638 (Scudder, 1876). Benjamin Franklin, who personally owned perhaps 4,000 volumes, was behind The Library Company of Philadelphia, access to which was available through the purchase of stock (Scudder, 1876).

| Peterborough Town Library, The First Public Library Photo Courtesty of the Town of Peterborough |

By the nineteenth century a wide variety of institutions, from factories to temperance societies, had made collections of books available to their members. In much the same way that firefighting was a private endeavor undertaken for the public good by competing companies with political and financial gain as openly acknowledged goals, so most libraries were formed and operated by private institutions with the aim of benefiting and gaining the gratitude of communities they hoped to influence and prosper in. (Scudder, 1876)

If we define a public library as a collection of information resources open to the general public, supported by taxes, and resting in the ownership of the polity in which it lies, the first public library is commonly considered the Peterborough Town Library founded in Peterborough, New Hampshire in 1833, as the library of a public college which failed to materialize. In 1835, New York tried to create libraries for each school district that would have been public, and similar legislation was enacted in at least eighteen other states, but the propositions were ill-conceived (Bobinski, 1969). The "social libraries" of New England which flourished from the end of the eighteenth to the middle of the nineteenth century were open to anyone who paid for access, and many such collection formed the nucleus of future public libraries, but it wasn't until 1848 that Boston purposefully undertook to create a tax-funded public collection in its own building for the purpose of improving the citizenry, and it was ahead of its time (Bobinski, 1969).

|

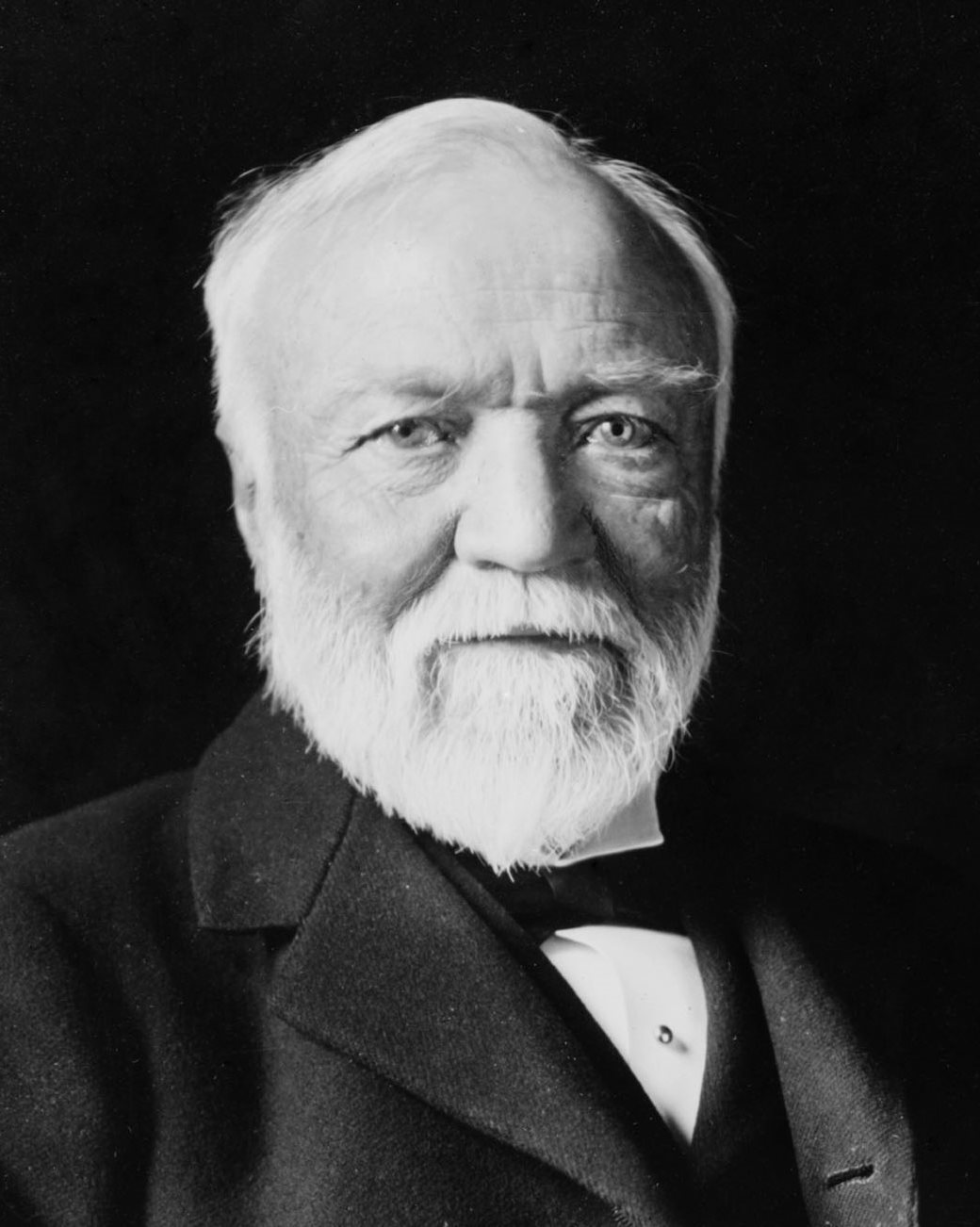

| Andrew Carnegie Photo by Theodore C. Marceau From the Wikimedia Commons |

The history of the Petaluma Free Library fits nicely into this history of public libraries, illustrating all the evolutionary stages described above. As this project will describe in depth, the library went from a small private library to a social library to a free public library, later participating in two larger, related philanthropic trends: the first being Carnegie’s creation of educational institutions to foster meritocracy and strengthen democracy, the second being The Free Library Movement which sought to replace saloons with a wholesome and constructive alternative venue for after-work recreation. The Free Library Movement, with its emphasis on the physical location of the library as a place of refuge from the temptations of the bar, helped redefine the library from being a collection of books to a civic institution housed in a pleasing public space (Scudder, 1876). In the 1890’s communities in the United States were to display an unusual degree of pride in such public spaces, attributable in part perhaps to the great excitement caused by the 1893 Colombian Exhibition held in Chicago which spawned the “City Beautful” Movement (Bobinski, 1969).

No comments:

Post a Comment